5.5 Glycaemic Index (GI) Diet

We have discussed in previous sections the importance of increasing daily vegetable intake for health. Proponents of the alkaline and Mediterranean diets have this as a common theme. What these diets also recommend, but do not place the main focus on, is reducing processed and sugary foods.

The Glycaemic Index (GI) style of eating, however, places its key focus on the carbohydrate (glucose or sugar) content of food. In Part 1, we discussed the structures of different carbohydrates. Remember that it’s not just sweet-tasting foods that contain glucose; starch found in vegetables and grains is also made up from chains of glucose units so also contribute to the GI (i.e. sugar) load of the diet so need to be balanced in order to maintain health. Removing high starch vegetables and grains is also part of the approach of the Paleo diet.

Managing the carbohydrate content of the diet is the most effective way to maintain steady blood sugar levels and the body’s hormonal response to blood sugar, i.e. insulin. There are many studies that show overconsumption of high sugar/starch (and processed) foods can contribute to chronic inflammation and many different disease states from insulin resistance, Type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obesity and cardiovascular disease. Please read the following reference that makes up part of the module content:

- Ludwig et al (2018) Dietary carbohydrates: role of quality and quantity in chronic disease. BMJ 316 Full Paper

Managing blood sugar levels, however, is not about complete avoidance/abstinence of carbohydrates, which would mean removing all vegetables and grains from the diet, as well as other sugar/starch sources. Remember that carbohydrates are an essential nutrient. You need carbs as they break down into glucose in your body providing the:

- Main fuel for our brains and nervous systems.

- Preferred source of fuel for most organs and our muscles during exercise.

This is why the Paleo style of eating does not suit everyone; some people report feeling low in energy, especially when starting out changing to a Paleo style of eating.

Remember though that it’s the type of carbohydrate consumed that is important – slow release or complex carbohydrates (e.g. porridge oats, beans) take time to digest and release glucose units into the blood stream compared to high sugar and starch foods, which cause a sudden spike in blood sugars. We will discuss the impact of dysregulated insulin and blood sugar imbalances on health in more detail in the next section (5.7) on Intermittent Fasting.

Therefore, the main principle of a GI diet is to consume low GI foods and reduce/avoid high GI foods, especially processed sugars and starches, to maintain an even blood sugar and insulin release and response.

The Glycemic Index ranks carbohydrate in foods according to how they affect blood glucose levels against the GI of glucose labelled as 100 units. Carbohydrates with a low GI value (55 or less) are more slowly digested, absorbed and metabolised and cause a lower and slower rise in blood glucose and insulin levels.

There are three ratings for GI in individual portions:

Low = GI value 55 or less

Medium = GI value of 56 – 69 inclusive

High = GI 70 or more

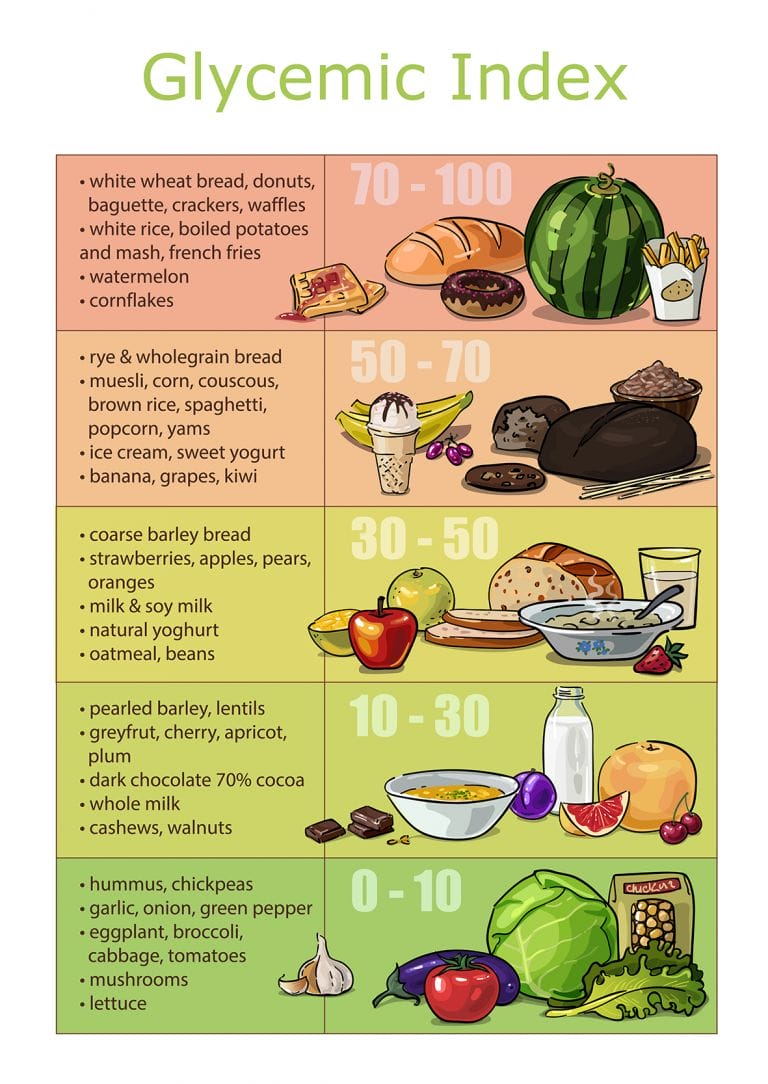

Figure 5.2 shows the food groups according to their GI level.

Table 5.2 shows the GI for specific foods:

| FOOD | Glycemic index (glucose = 100) | FOOD | Glycemic index (glucose = 100) |

| HIGH-CARBOHYDRATE FOODS | BREAKFAST CEREALS | ||

| White wheat bread | 75 ± 2 | Cornflakes | 81 ± 6 |

| Whole wheat/whole meal bread | 74 ± 2 | Wheat flake biscuits | 69 ± 2 |

| Specialty grain bread | 53 ± 2 | Porridge, rolled oats | 55 ± 2 |

| Chapatti | 52 ± 4 | Instant oat porridge | 79 ± 3 |

| Corn tortilla | 46 ± 4 | Muesli | 57 ± 2 |

| White rice, boiled | 73 ± 4 | ||

| Brown rice, boiled | 68 ± 4 | FRUIT AND FRUIT PRODUCTS | |

| Barley | 28 ± 2 | Apple, raw | 36 ± 2 |

| Sweet corn | 52 ± 5 | Orange, raw | 43 ± 3 |

| Spaghetti, white | 49 ± 2 | Banana, raw | 51 ± 3 |

| Spaghetti, whole meal | 48 ± 5 | Pineapple, raw | 59 ± 8 |

| Rice noodles | 53 ± 7 | Mango, raw | 51 ± 5 |

| Udon noodles | 55 ± 7 | Watermelon, raw | 76 ± 4 |

| Couscous | 65 ± 4 | Dates, raw | 42 ± 4 |

| Peaches, canned | 43 ± 5 | ||

| VEGETABLES | Strawberry jam/jelly | 49 ± 3 | |

| Potato, boiled | 78 ± 4 | Apple juice | 41 ± 2 |

| Potato, mash | 87 ± 3 | Orange juice | 50 ± 2 |

| Potato, french fries | 63 ± 5 | ||

| Carrots, boiled | 39 ± 4 | LEGUMES | |

| Sweet potato, boiled | 63 ± 6 | Chickpeas | 28 ± 9 |

| Vegetable soup | 48 ± 5 | Kidney beans | 24 ± 4 |

| Lentils | 32 ± 5 | ||

| DAIRY PRODUCTS AND ALTERNATIVES | Soya beans | 16 ± 1 | |

| Milk, full fat | 39 ± 3 | ||

| Milk, skim | 37 ± 4 | SNACK PRODUCTS | |

| Ice cream | 51 ± 3 | Chocolate | 40 ± 3 |

| Yogurt, fruit | 41 ± 2 | Popcorn | 65 ± 5 |

| Soy milk | 34 ± 4 | Potato crisps | 56 ± 3 |

| Rice milk | 86 ± 7 | Soft drink/soda | 59 ± 3 |

| Rice crackers/crisps | 87 ± 2 | ||

| SUGARS | |||

| Fructose | 15 ± 4 | ||

| Sucrose | 65 ± 4 | ||

| Honey | 61 ± 3 | ||

| Data are means ± SEM. | |||

The complete list of the glycemic index and glycemic load for more than 1,000 foods can be found in the article “International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008” by Fiona S. Atkinson, Kaye Foster-Powell, and Jennie C. Brand-Miller in the December 2008 issue of Diabetes Care, Vol. 31, number 12, pages 2281-2283.

You can see from the figures in Table 5.2 that it’s not just the chemical structure of the carbohydrate source that affects its GI value. The style of cooking can also affect carb structure and therefore alter the GI content of food; for example, the GI of different forms of cooked potatoes (e.g. mashed versus boiled) is affected due to starch breaking down into glucose during extensive baking rather than boiling. Fat and fibre content of food also slows down the sugar absorption from the digestive tract therefore lowers the GI of foods (e.g. French fries). However, this does not mean that these foods can be freely eaten! Common sense needs to still apply to over-consumption of processed foods for cumulative health reasons.

Simply taking the GI of a food, i.e. its ability to raise blood glucose levels, is not actually the full picture. Your blood glucose levels rise and fall when you eat a meal containing carbohydrates. How high it rises and how long it stays high depends on the quality of the carbohydrates (the GI) as well as the quantity. Glycemic Load (or GL) combines both the quantity and quality of carbohydrates. It is also the best way to compare blood glucose values of different types and amounts of foods. The formula for calculating the GL of a particular food or meal is:

Glycemic Load = GI x Carbohydrate (g) content per portion ÷ 100.

For example, a single apple has a GI of 38 and contains 13 grammes of carbohydrates.

GL= 38 x 13/100 = 5

A potato has a GI of 85 and contains 14 grammes of carbohydrate

GL=85 x14/100 = 12

We can therefore predict that the potato will have twice the glycemic effect of an apple.

Similar to GI, the GL of a food can be classified as low, medium, or high:

Low: 10 or less

Medium: 11 – 19

High: 20 or more

GI or GL?

Although the GL concept has been useful in scientific research, it’s the GI that’s proven most helpful to people with diabetes and those who are overweight. That’s because a diet with a low GL, unfortunately, can be a ‘mixed bag’ full of healthy low GI carbs in some cases, but too high in protein and low in carbs and full of the wrong sorts of fats (i.e. saturated fats) such as those found in some ‘discretionary foods’.

If you use the GI as it was originally intended – to choose the lower GI option within a food group or category – you usually select the one with the lowest GL anyway because foods are grouped together for a reason because they contain similar nutrients, including amounts of carbohydrate. So, if you choose low GI foods (ideally with GI score less than 40), chances are you’re eating a diet that not only keeps blood glucose more on an even keel but also contains balanced amounts of carbohydrates, fats and proteins.

Artificial Sweeteners & GI

One of the main questions that is often asked is if sugar is reduced in the diet, can artificial sweeteners be used instead? Many low sugar foods include artificial sweeteners to make them palatable, including in fruit squashes and tonic water/drink mixers. However, studies suggest that artificial sweeteners may not be benign in the body. In fact, they may impact areas such as our gut microbiota. At nutrihub, we think that the clue is in the name – they are “artificial” and therefore do not play a role in health and could even be classed as a toxin, as described in Part 1 of the Advanced course. Please read the following article, which makes up part of the module content:

GI diet summary

- A low GI diet can help people to improve blood glucose levels and insulin response, especially in conditions such as insulin resistance, Type 2 diabetes and weight management.

- A GI table of foods can be used to stick to consuming mainly foods with GI less than 55 (i.e. low GI foods).

- Focus is on low starch vegetables rather than fruits.

- Low GI grains are permitted in this nutrition plan but may need to be addressed as they still raise blood sugar and insulin levels and also in cases of food sensitivities, IBS etc. (discussed in section 5.8).

| Advantages/ Benefits | Disadvantages | |

| GI Diet | Increasing vegetable intake improves nutrient and fibre content. | Foods with low GI <55 include grains such as rice and pasta, which still contain sugars so spike insulin. Reducing grain, starchy vegetable and fruit intake as per Paleo style diet is therefore often recommended over and above GI diet. |

| Reducing processed foods and refine sugar. | Difficult to remember which are low GI foods – need access to low GI foods table when cooking and eating. | |

| Fits into many people’s perception of a healthy diet and all foods easy to source. |

Please make sure you’ve read the articles and references that make up some of the content of this section:

- Artificial sweeteners, microbes and blood sugar control

- Ludwig et al (2018) Dietary carbohydrates: role of quality and quantity in chronic disease. BMJ 316 Full Paper

- 5.1 Alkaline Diets

- 5.2 Vegetarian & Vegan Diets

- 5.3 Mediterranean Diets

- 5.4 Paleo Diet

- 5.5 Glycaemic Index (GI) Diet

- 5.6 Anti-inflammatory and Auto-immune Diet

- 5.7 Intermittent Fasting & Time Restricted Feeding (TRF)

- 5.8 FODMAP Diet

- 5.9 What Next? Developing Your Own Approach to Functional Nutrition

- 5.10 Module Summary

- 5.11 Recommended Reading & References

- 6.1 What Are Phytonutrients?

- 6.2 Phytonutrient Groups

- 6.3 Evidence For Phytonutrient Anti-Disease Activity

- 6.4 Curcumin

- 6.5 Cannabidiol (CBD) oil

- 6.6 Ashwagandha

- 6.7 Aloe Vera

- 6.8 Supergreens (Alkalising) powders

- 6.9 Gut Supporting Botanicals

- 6.10 Phytonutrient Supplementation

- 6.11 Herbal Laws

- 6.12 Module Summary

- 6.13 Recommended Reading & References

- 7.1 Do We Need Food Supplements?

- 7.2 Nutrient Dietary Reference Values (DRVs)

- 7.3 Vitamins

- 7.4 Minerals

- 7.5 Bioavailability of Food Supplements

- 7.6 Multi-nutrient Formulations

- 7.7 Gut Bacteria

- 7.8 Digestive Enzymes

- 7.9 Saccharomyces boulardii

- 7.10 Essential Fatty Acids

- 7.11 Directional Supplements

- 7.12 Combined Programme

- 7.13 Module Summary

- 7.14 Recommended Reading & References